|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Aeronautics and Astronautics at Stuttgart By Bjoern Schirmeier Daring men in their flying machines, airborne acrobatics in and on top of biplanes, pictures of planes flying war missions: there are many ways of approaching the subject of aeronautics. Since 1956 there has been an ideal way of doing so. Studying Aeronautics and Astronautics at the Universität Stuttgart provides access to the design, manufacture and use of the fascinating world of aircraft.

Daring menThe history of flight begins like any other technical discipline with a "trial-and-error" phase, in which actions by isolated individuals bring about the results that are so desperately needed. The move towards a more scientific approach pushes these spectacular individual events into the background, but also provides a broader foundation for the discipline.

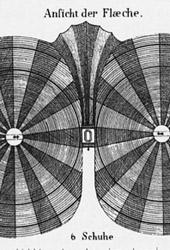

Zeppelin and his influence on StuttgartWhen in December 1903 in Kittyhawk, USA the Wright brothers' Flyer I took off on its maiden 50m flight, hardly anyone in Europe took notice. Especially in the German Reich, Count Zeppelin with his airships, which were seen as a "product of Swabia" by the Württemberg population, was the undisputed star on the aviation stage. Only five years later the situation had changed. In 1908 Louis Bleriot flew over the English Channel, and the aeronautical principle of "Heavier than air" was seen as a serious alternative to that of "Lighter than air". Thus it was only a matter of time until the first steps were taken towards making the field more scientific in its approach, especially as the Kingdom of Württemberg considered itself a pioneer in aviation. And thus efforts were soon being made to establish a university chair in the field. When the Zeppelin Memorial Foundation donated a sum of money with this aim in mind in 1911, the Chair of Airship Aviation, Aeronautics and Motor Vehicles (Professur für Luftschifffahrt, Flugtechnik und Kraftfahrzeuge) could finally be established. Alexander Baumann took over the chair, thus becoming the first full professor of aeronautics in the German Reich. Baumann had held his first lectures as early as 1910, even before his appointment to the post. After his appointment, he ambitiously began to expand the discipline. Thus in 1912 he acquired a two-seater Wright aircraft as a teaching aid. His other duties included serving the central Württemberg authorities as an expert advisor. Background information: "Lighter than air" The lift for the aircraft (balloon, airship, etc.) is created using a gas whose density is lower than the surrounding air. Mainly hydrogen, helium or hot air are used. Background information: "Heavier than air" In this case, the aircraft has to cope without any supporting medium, like a gas (see the "Lighter than air" principle). For example the lift is supplied here by air currents on the wings of the aircraft. Background information: Zeppelin Memorial Foundation A registered association, founded by shareholders in the Zeppelin company. Background information: Chair of Airship Aviation, Aeronautics and Motor Vehicles The first two fields stand for the two principles of "Lighter than air" and "Heavier than air", respectively. The last field also covers propulsion engines and is thus also part of aeronautics.

From one war to the nextDespite the restrictions the Versailles Peace Treaty of 1919 envisaged for Aeronautics in the Weimar Republic, Stuttgart College of Technology was able to create a profile for itself as a centre of scientific teaching. Yet students with an interest in the subject could only study Aeronautic Engineering as an optional course within a course in Mechanical Engineering. Important developments took place in aeronautic engineering during the time shortly before and after the National Socialists took power. In 1929, after Baumann's death, his department was split in two, giving rise to the Stuttgart Aeronautic Engineering Institute (Flugtechnisches Institut Stuttgart, FIST) on the one hand, headed by Georg Madelung, who thus became Baumann's successor, and the Research Institute for Automotive Engineering and Vehicle Engines (Forschungsinstitut für Kraftfahrwesen und Fahrzeugmotoren, FKFS) on the other hand, founded in 1930. Wunibald Kamm was appointed head of the latter institute. This expansion of research activities led in turn to an expansion of teaching activities, which was also in the interests of the expanding military state. In the summer semester of 1936, the subject of Aeronautical Engineering was then offered for the first time. However, introductory courses still had to be taken in the Mechanical Engineering department. During the war aeronautic research was extended within the German Reich as a whole after the failure of Germany's blitzkrieg strategy. In 1941 the Count Zeppelin Research Institute (Forschungsanstalt Graf Zeppelin, FGZ) was formed to support this aim. The head of this institute was also Georg Madelung.

Zero hour?During the Second World War many institutes of the College of Technology were evacuated from Stuttgart out of fears that they might be destroyed in air raids. When hostilities finally ceased in 1945, 75% of the college had been destroyed. Research in aeronautics was almost completely banned by the Allied Control Council: it had to be reported to the authorities and was subject to the Allies' constant control. The denazification process had not been completed when the college recommenced research and teaching in February 1946. In 1946 the Aeronautic Engineering Institute (FIST) and Count Zeppelin Research Institute (FGZ) were transformed into the Construction Research Institute at Stuttgart College of Technology (Bauforschungsanstalt an der Technischen Hochschule Stuttgart).

Step by step back into the airThe redevelopment of aeronautic engineering began very soon after the end of the war. In addition to concentrating the various institutes at one site, the course of study was also to undergo changes.

A new start and new profileAfter the end of the war many German research institutions were disbanded by the Allied Control Council. These also included the German Aviation Testing Unit (Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt, DVL) based in Berlin. One of the DVL's many institutes was the Institute for Gas Dynamics, headed by Arthur Weise. As the institute was now literally "up in the air", Weise set off in search of a new home. Stuttgart College of Technology showed an interest in employing him, even though funding was very scarce at the time. Weise would thus only be able to employ two assistants and a technician. Despite this he decided to move to Stuttgart. The move took place in 1946/47 and brought the institute from Sonthofen, where it had been evacuated to, to Ruit above Esslingen, the former site of the FGZ. Having arrived there, the first concern was to furnish the offices and workshops in preparation for recommencing research. After 1945 aerodynamic research was strictly forbidden by the Allies. Weise did not just make efforts to reinstate aviation at Stuttgart in the years that followed. Renowned engineers such as Eugen Sänger and Heinrich Focke moved to Stuttgart for a short time and founded institutes, which, although they were only short-lived, brought a new impetus to the college. Thus the new Institute for Gas Currents under Arthur Weise became a focal point for new aviation research in Stuttgart. Background information: German Aviation Testing Unit Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt (DVL) - a state-run non-university research institution. It was founded in 1912, and its headquarters were in Berlin-Adlershof. Background information: Eugen Sänger He specialised very early on (around 1930) in rocket aircraft engineering. In 1954 he founded the Research Institute for the Physics of Jet Propulsion at Stuttgart College of Technology. He developed the eponymous Sänger principle for astronautical systems. Background information: Heinrich Focke He was the co-founder of the Focke-Wulf Aircraft Engineering Company. He was to become a Full Professor at Stuttgart College of Technology but did not accept the appointment.

A new site is bornIt was not until 1955 that the Allies lifted the last research bans, which still covered many areas of aviation. Yet despite this new-found freedom the problem of a lack of space remained. Teaching and research had to be conducted at separate sites. When the decision was made in 1956 to create a new university site at the Pfaffenwald area, building work began straight away. The first buildings were completed in 1959. Now the testing and teaching facilities (design studios, photo laboratories, etc.) could gradually be brought under one roof. Much of the work was done by students and lecturers on a volunteer basis. Between 1960 and 1969 the most important buildings were constructed for the new institutes. This construction phase saw the creation of five institutes: Aerodynamics and Gas Dynamics; Aircraft Construction; Statics and Dynamics of Aeronautic and Astronautic Structures; Thermodynamics of Aeronautics and Astronautics; and Turbo Aircraft Engines. Background information: research bans After the end of the war, the victorious Allied powers imposed extensive research bans throughout Germany. These bans were gradually lifted between 1945 and 1955 and were eventually abolished completely on the ratification of the German State Treaty (Deutschlandvertrag) of 1955.

Now we've got the space, what about a course of study?The expansion of the scientific discipline now urgently needed to be complemented with a full course of studies. As early as the 1930s, the German Aviation Ministry had envisaged Stuttgart College of Technology as a training centre for aviation engineers. These plans had not been shelved in the post-war period. The Ministry of Culture in Stuttgart continued to plan the college as a centre for teaching aviation engineering. Thus in 1955 a separate department of Aviation Engineering and a corresponding course of studies was founded within the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering. Now for the first time it was possible to start studying Aeronautic and Astronautic Engineering from the very first semester, and not only from the fifth semester onwards after passing the intermediate exam, as had previously been the case. This new course got underway in the winter semester of 1956/57. Provisions had only been made for 60 students a year, a figure which was quickly exceeded by growing numbers of first-year students, and thus the old problem of lack of space soon returned. Due to a lack of teaching capacity, between 1956 and 1960 students still had to complete their introductory studies in Mechanical Engineering. It was only when further buildings were completed and new professors were appointed that introductory studies could be carried out by the department itself from the winter semester of 1960/61. Astronautic Engineering had been taught in Stuttgart since the late 1950s. But it was only as part of the reorganisation of the faculties in 1969 that the expansion of astronautic research was reflected in the university structure. The new faculty and course of studies were given the name of Aeronautic and Astronautic Engineering. Background information: German Aviation Ministry In 1935 the German Aviation Ministry devised a plan to develop Stuttgart into a teaching centre for aeronautic engineering alongside Aachen, Munich and Berlin. All that the German Education Ministry, under whose authority such plans ought to have fallen, could do was to acquiesce to the proposal.

Egyptian gods and Greek mythsWhen Albrecht Ludwig Berblinger tried and failed to fly over the Danube in a glider in 1811, he became the laughing stock of his fellow citizens. As he devised his plans, it probably never occurred to him that one day a prize would be offered in honour of the famous "Schneider von Ulm" (tailor of Ulm) ...

A tailor leads the wayThe Berblinger Prize was first awarded in 1986 for emulating Berlinger's attempt to fly over the Danube in an identical glider. Many failed, but a few participants did actually manage to cross the river without getting their feet wet. Due to the great success of this competition, the city of Ulm decided to award the prize every two years for special achievements in aviation. These prizes were not bound to a specific topic; any achievement in the field of aviation could be considered. Then in 1992 again a specific task was set: "Who can build the best solar aircraft?" Even before the prize was advertised, the jury had approached the universities of Ulm and Stuttgart to check whether the requirements could actually be fulfilled. This work was carried out in research for student diploma dissertations demonstrating the feasibility of individual components. The participants then had time until 1996 to construct a fully functional solar aircraft. In addition to fulfilling many technical requirements, the aircraft also had to be capable of being put into practical use. Background information: solar aircraft The first solar powered aircraft took to the air in 1972. Energy supplied by the sun is fed into an electric motor, which in turn powers the aircraft. Yet until the 1990s solar aircraft were still experimental. Many prototypes were either extremely fragile or very primitive in design. They could only be used in ideal weather conditions. Thus everyday use was out of the question.

A project for everyoneAfter it had been proven that solar aircraft were generally feasible, participants from many countries began to register for the competition and send their project designs to Ulm. The Faculty of Aeronautic and Astronautic Engineering in Stuttgart also decided to take part in this competition. A project group was founded within the faculty with this objective in mind. The participants included both teaching staff and students. Many parts of the aircraft were developed by the group itself. The propeller, for instance, was developed specially, as were the fuselage and the wings. Much of the research for this was conducted by students in term papers and diploma dissertations. The results of this work were directly fed into development. This project group gave rise to around 40 term papers and diploma dissertations. The individual institutes made their facilities available for measurements and calculations. The aircraft was assembled at the Institute for Aircraft Engineering. A prototype was developed and constructed to check the initial design. This aircraft, which was called Icare, was planned as a muscle-driven plane. After many concepts had been successfully tested in this study, construction of the solar craft itself began, which was then given the name Icare II. The name is a combination of Icarus, the figure of Greek legend, and the Egyptian sun god, Re.

Icare II is cleared for take-offThe competition rules required construction plans to be submitted in 1995 and the completed aircraft to be tested on 1 May 1996. But none of the competitors were ready by this date. The test flight date was then set for 7 July 1996. The participants were to present their completed solar aircraft as part of an air show at the German Airforce airfield in Laupheim. The aircraft were then assessed in their actual state. They were also to compete against each other in a flying contest. Yet the flying contest had to be cancelled, as Icare II was the only craft to be completed. Yet the plane was able to demonstrate its airborne skills in a series of show flights. Although some of the jury's requirements were not met, Icare II was awarded the first prize of DM 100,000.

The gains from taking part in the competition cannot simply be expressed in terms of money. The term papers and diploma dissertations have already been mentioned, and this project also gave rise to some PhD theses and patents. The participants in the Icare project had the opportunity to work on an interdisciplinary and professional high-tech venture.

Icare II flies onThe Berblinger Prize was not the end but only the beginning of the technological developments brought about by Icare. The aircraft was subsequently modified, and new equipment was installed to improve flight performance. When another test flight was scheduled for 17 June 2003, no one could have guessed that a special surprise was in store. The aircraft took off from Aalen-Elchingen, and as everything was working perfectly the pilot decided to fly further than initially planned. When he finally landed in Jena at 5 p.m., he had set a new world record. Never before had a solar glider flown so far (350 km) at one time.

Further information and pictures can be found on the web site:

Biography: Aeronautic and astronautic engineering in Stuttgart (born 1910)

|

|

Last updated 04/10/2006 ( |