For trained professionals, the digitalization and networking of production facilities is “the Fourth Industrial Revolution" - following on the heels of the steam engine, the assembly line, and the introduction of EDP. This in turn has given rise to "Industry 4.0," a term for intelligent solutions that can process and evaluate masses of data. These modern forms of technology will drastically change company workplace environments. Employees must be more flexible in future - but can also take over more responsibility.

Engineers today stand in their labs and discuss how to design their new robot. Where should the rocker arm go? The axles? What movements must it carry out? Words are almost inadequate to explain such issues - and technical drawings are complex. The engineers respond by donning spectacles that at first glance resemble ski goggles. But these are not sport articles, but rather "mixed-reality" spectacles. They enable the wearer to guide three-dimensional projections with only small gestures that change the image on the screen. The other team members follow with their own spectacles, which have small, transparent screens. In this way, the team sees how the axes of the robot which is displayed wander from one place to another and how the gripping arm swings to various positions. Just as in an interactive video game, each member of the group can make changes in the image currently displayed.

Scenes like this are still fiction. But it may not be long before they dictate daily routine in companies which design and manufacture machines and systems. And not only in their development departments. This could give even employees who are unaccustomed to think in terms of three-dimensional space the possibility of helping to plan work steps. The right place for a machine? The optimum mode of operating tools? Questions like these could then be answered in only a few words.

The "mixed-reality-spectacles" show how an adroit use of modern technology might benefit the working world of tomorrow. "Technical meetings would become more efficient, and it would be easier to present and implement ideas," says Thilo Zimmermann, a project leader at Future Work Lab, an "innovation laboratory" with a focus on the working world, the worker, and technology. Here several institutes of the University of Stuttgart have joined the Fraunhofer Institutes for Industrial Engineering (IAO) and for Manufacturing Engineering and Automation (IPA) to synergize their mutual areas of competence regarding networked production.

Advantages and risks of the digital working world

The football-field-sized ARENA2036 research facility is a salient feature of the University of Stuttgart campus. It acts as a flexible "research factory," providing support for the development of products and production methods for Factory 4.0. The visitor sees fresh-plastered walls with shiny metal pipes near the ceiling. Daylight streams through a glass roof into the interior. It looks like a factory built by an iPad designer: bright and radiant

The men and women doing research here have their offices on an upper first-floor gallery. These professionals come not only from the engineering branches but also from the fields of applied economics and the social sciences. The projects which have brought them together aim to show how daily work in a digitized company might look, what advantages it has, and where risks lie in wait.

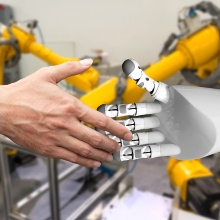

The teams at Future Work Lab have already turned more than a dozen ideas into demonstration objects. "We want to give a concrete impression of how the working world of tomorrow might look," says Zimmermann as he points to a bright orange-coloured robot. Until now, machines like this were allowed to work only behind a protective fence, since a blow from their steel arms could be life-endangering. Now, however, the display model in the "research factory" exhibits a perfectly safe solution: the robot is not fully automatic, but can be guided by means of a "steering wheel" - much as reins are used to guide a horse. The force exerted by the user determines the power of the robot's movements. The result is not a fully automatic creation which renders human beings superfluous but rather quite the contrary: "The robot becomes the colleague," says Zimmermann. "The dexterity of man is united with the strength of the robot."

No factories without human beings

Development thinkers in the areas of machine and systems engineering have racked their brains for years to find more efficient processing designs. In the 1980s, for example, production planners came up with radical concepts, and "Computer Integrated Manufacturing" was the watchword. The target was to design a factory devoid of human beings, where products rolled out fully automatically. Controllers liked the idea, but the trade unions saw it as a sheer disaster. And Thomas Bauernhansl says today that it will never happen. He is a professor who heads up the University of Stuttgart's Institute for Industrial Production and Factory Operations (IFF) and has spent many years exploring issues involved in Flexible Production. At the same time, he believes that work in industrial enterprises is facing major changes, and that the classic industrial worker of the 19th and 20th centuries - the person standing at the assembly line, endlessly performing the same act - will soon belong to the past.

As digitalization spreads, on the other hand, work scenarios will become more demanding: the person at the machine, who was traditionally responsible for only one step in the process, will in future control electronically guided machine systems while also looking for ways to make the production process more efficient. "Stand-alone work operations will grow fewer," says Bauernhansl: "Each worker will become a director who orchestrates the added value process."

Management today is becoming more and more aware that the worker at the basis is often the person who best knows how work steps should be organized. After all, he/she is often the one who has been at the same post for decades and knows every detail of the surroundings. In the past, this person was often only a factotum, while management took care of production planning and passed down its pronuntiamentos in classical fashion from top to bottom. The results were predictable: The person at the work station felt passed over, which in turn engendered frustration and flagging motivation. In the working world of tomorrow, in contrast, workers might have a hand in the planning process.

The production plant of tomorrow will, as it were, organize itself through digital technology. Michael Reutter is one of those thinking about how this will look in actual practice. After graduating in Machine Design and Construction from the University of Stuttgart, this budding young entrepreneur went on to work at the Fraunhofer IAO and then, a good year ago, founded his own company with a friend and named it "Aucobo". "Our aim is to give the worker at the basis instruments that enable him or her to profit from digitalization." Reutter reports that modern production plants increasingly tend to curtail both incentives for employees and support for them on the career ladder. People are organized like pieces on a board, with no way to contribute the know-how they have often gathered over decades. "That's not the way to exploit the possibilities of digitalization," says Reutter. Today's industrial software can be designed for use even by persons who have no expertise with IT. After all, he points out, anyone can use a smartphone or a tablet without prior training. The basis of his program is a standard commercial smartwatch with stand-alone functions, that is, with no need of an external smartphone.

Overcoming the lack of skilled workers

The worker can use it to put together his/her own app. "It's like using a digital toolbox, much like the one used to create one's own website,," says 29-year-old Reutter. Whereas it was once quite difficult to create a personal Internet page, "Practically anyone can do it today," says Reutter. In fact, this is how Reutter and his partner programmed a mobile machine control program which can be guided intuitively via app. The app can be used, for example, in production plants where one worker is in charge of several processing steps, such as pressing, clamping, and/or glueing.

In the past, such a worker watched three machines at the same time, inserting insert material on time, adding needed components, and taking out finished parts at the end. In time this became routine, but with one disadvantage: machine downtimes whenever the worker was occupied somewhere else. Now, however, the smartwatch can sound an alarm to remind him of tasks which need immediate attention, as when a machine must be reloaded. Even when he is in another production area, he hears the humming signal and can return at once or press a button to ask a colleague to take over the task for him. This does more than merely make communication between the human being and the machine more effective: consultation with colleagues and documentation is simplified as well. "In future, information about individual machines could be stored with electronic solutions of this type," says Reutter. While technology takes care of individual cases, the worker can store remarks at a central location so that valuable knowledge is not lost when the employee leaves the organisation. Festo, the specialist company for control and automation technology, has already put the smartwatch from Aucobo to use at its plant in the German city of Esslingen, for example. This pilot project involved seven volunteer employees in the company's valve production area. "The feedback was invariably positive," says Reutter. No reservations were voiced, quite the contrary: "Other workers heard of the pilot test, saw the smartwatch on the arms of their colleagues, and wanted one too." But it was more than a charming design which aroused the interest and enthusiasm of the users.

Observers like Bauernhansl see it as a must that employees become enthused about technological progress. "After all," he says, "all developments come in the long run from human beings. The more they enjoy such progress, the higher the quality of the results. One of the primary tasks, therefore, is to continue the training of relatively untrained employees so that they can take over more demanding jobs in future. The alternative is a lack of workers: "We would run out of the trained workers we need for our production plants to function as well as possible." And just how many workers will be needed in the networked production plants of the future? Opinions vary widely. Four years ago, a scientific study on the subject caused a small upheaval in the working world: Carl Benedikt Frey, a professor at the University of Oxford, and his colleague Michael Osborne estimated the likelihood that work in certain professions will be carried out in the coming 20 years by new forms of technology. In Germany alone, this would threaten the existence of 59 percent of jobs. On the other hand, the Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW) came to quite a different result: experts there calculated with about the same degree of probability that only 12 percent of jobs in Germany could be automated.

Man and machine: a single working unit

For Bauernhansl there is no doubt that digital production in the age of Industry 4.0 will require fewer human workers. While this in turn will go far to defuse the serious dearth of trained workers, there's even more to think about: "As interaction increases, intelligent machines will merge with the workers to form an integrated production system." This can already be seen in very elementary forms of work. For example, omnibus manufacture requires that heavy cable bundles be installed overhead in the vehicles. This is hard work, and only young, physically fit men could do it up to now.

In future, however, even older employees could be considered for it. It would then be up to them to decide whether to do the work with or without technical aids. If they feel that their strength is inadequate, a powered exoskeleton like the one on display in the Future Work Lab might be provided for them. Worn like a ten-kilogram corset, its battery-powered mini-motors take over the exertion of small movements and make it easier for human beings to carry out heavy-duty work in awkward positions. In future, machines will thus take over the task of directly providing daily on-the-job support to the worker. This even affects the learning phase: "Classical, protracted training on the shop floor will be supplanted by ad-hoc training on-the-job," says Bauernhansl. One way to do this would involve user-operated displays with precise, clear user guidance and accompanying training videos.

A work station at the Future Work Lab gives a concrete idea of how machines might train their users: sensors attached to the worker detect his bodily position; after analysis, the machine recommends less strenuous ways of carrying out the work, e.g. by bending the knees more, lifting the chin, or standing straighter. It might even be possible one day to simplify this technology and integrate it, for example, into a T-shirt. It will also be possible to leave it up to office workers in future how to organize their work with electronic aids. Here too, the "Research Factory" shows what an office desk of the future might look like. The person at the desk simply uses his/her hands to make contact with a touchscreen covering nearly the whole of the desktop. The virtual diagrams there can be opened up with swipe movements and reorganized endlessly, just as on a sheet of paper: adjacent to one another, in stacks, or fanned out.

These electronic diagrams can be folded, rotated, and laid on their sides. The apparent chaos on the desk can be brought to order instantly and then logically stored with a click. To be successful in the new digital working world, it will be important not to be distracted by fascinating technology. Professor Bauernhansl's advice: be systematic. "Start with an idea for a business model," says he, then work out the technological concept in a second step, but only when it has become clear what it will be needed for. After that, develop the clientele and the market parallel to the technology. "Then get the entire organisation involved." This is the guiding principle for both the company culture and the employee abilities. If for example a company's sales area has been selling machine components for years, it must first gain the ability to offer future customers platform-based services. Digitalization is thus not an end in itself; rather, it must be guided by business logic. This applies just as much for guided robots and smart wrist watches as for mixed-reality spectacles.

Heimo Fischer